On the 5th of July 1909, female self-starvation became politicised as WSPU member Marion Wallace Dunlop initiated a hunger strike within Holloway Goal. Suffragettes famously embarked upon this strike in order to protest their confinement and punishment for public acts of physical insubordination that included breaking windows and chaining themselves to railings. Their rejection of food was a reaction to the government’s refusal to grant them the status of political prisoners. Rather than taking notice of and meeting the hunger strikers’ demands, however, the authorities responded with forcible-feeding.

On the 5th of July 1909, female self-starvation became politicised as WSPU member Marion Wallace Dunlop initiated a hunger strike within Holloway Goal. Suffragettes famously embarked upon this strike in order to protest their confinement and punishment for public acts of physical insubordination that included breaking windows and chaining themselves to railings. Their rejection of food was a reaction to the government’s refusal to grant them the status of political prisoners. Rather than taking notice of and meeting the hunger strikers’ demands, however, the authorities responded with forcible-feeding.

The late Victorian contest for control of the female body reaches its apogee in the battle for woman’s suffrage. The female mouth, in this instance, which has been open in protest and then closed in resistance, becomes a site that embodies the sexual and political violence always present but often hidden in nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century discourse on women’s ‘aberrant’ eating behaviours.

The hunger strikes that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century were not isolated incidents but were a product of the Victorian debate surrounding female eating habits. Women’s dietary requirements were monitored throughout the 1800s when there was much discussion upon the subject of what was appropriate for a woman to participate in or consume. According to newspaper articles and etiquette guides, women ought to eat less than men, while certain foods were considered altogether unsuitable. These restrictions that were placed upon the female body possessed a moral dimension since appetite was connected with sexuality. Woman’s hunger and consumption were therefore subject to constant regulation.

When the Women’s Social and Political Union was founded in 1903, its members endeavoured to gain recognition as subjective individuals, rather than submit to being defined in terms of their physiological form. One of the aims of the WSPU was to alter the perception that women were closely connected with their bodies. Ironically, this was achieved by starving the very object by which they were defined. Since it was problematic to classify women using bodies that were severely diminished by hunger strike, self-starvation contested the relationship between women and their physical form. The suffragettes used this bodily presence / absence to obtain a political and public existence.

Suffragettes campaigned for sexual equality and to alter patriarchal perceptions of women. Bodies were central to this agenda, Lucy Bland arguing that the suffrage movement aimed to achieve ‘the eradication of women’s experience of sexual objectification, sexual violence, and lack of bodily autonomy’. Medico-legal structures justified denying women admission to ‘masculine’ social and political spheres by pointing to the female body’s natural physical weakness in comparison to its masculine counterpart and arguing that a woman’s energy should be preserved for conceiving and bearing children.

to this agenda, Lucy Bland arguing that the suffrage movement aimed to achieve ‘the eradication of women’s experience of sexual objectification, sexual violence, and lack of bodily autonomy’. Medico-legal structures justified denying women admission to ‘masculine’ social and political spheres by pointing to the female body’s natural physical weakness in comparison to its masculine counterpart and arguing that a woman’s energy should be preserved for conceiving and bearing children.

The nineteenth century woman was defined in terms of her use as a reproductive entity. The productive capabilities of the female body and its social and political application are articulated by Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, within which he argues that the ‘political investment of the body is bound up, in with its economic use; it is largely as a force of production that the body is invested with relations of power and domination’. Perceived as objects that produce, rather than subjects who consume, a power dynamic was established in which women were reduced to their physical form and thus denied a political and legal existence. Foucault asserts, however, that this subjection was necessary in order to maintain women’s situation as productive beings: its constitution as labour power is possible only if it is caught up in a system of subjection…the body becomes a useful force only if it is both a productive body and a subjected body.

Prior to the suffrage movement, women who were restricted by their role as producers protested this situation by engaging in self-starvation which suspended the body’s ability for production. The refusal to eat functioned as a female protest tactic throughout the nineteenth century and reached its climax in the hunger strikes of 1909. Women’s bodies that had been exploited for their reproductive capacities were reclaimed by the suffragettes, who, like their mothers and grandmothers before them, aimed to achieve emancipation from domestic life, taking their campaign to extreme measures using militant protest.

Jane Marcus develops the concept of rejecting these traditional female roles that were connected with the body, arguing that ‘[w]hen woman, quintessential nurturer, refuses to eat, she cannot nurture the nation.’ In a ‘symbolic refusal of motherhood’, the suffragettes refused to be defined in terms of the body and its capacity for bearing and nurturing children. In doing so, they challenged woman’s social responsibility of caring for the family, which in turn served as a microcosm of the state. Rejecting their maternal position within the familial sphere through self-starvation was therefore also a threat to the future of society as a whole.

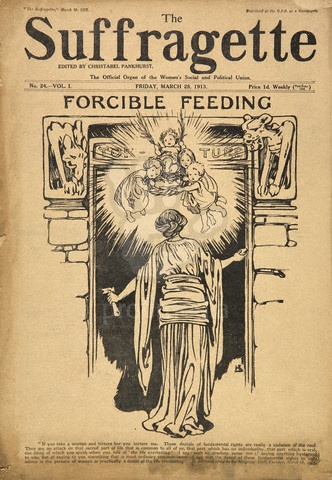

Prior to the nineteenth century, bodies were publicly exploited to exemplify unlawful behaviour. Punishment was a universal spectacle that focussed upon the body with frequent executions and branding of criminals. However, during the 1800s, ‘the great spectacle of physical punishment disappeared; the tortured body was avoided; the theatrical representation of pain was excluded from punishment.’ The suffragettes revived the spectacular element of punishment by bringing the suffering body back into the public view through inflicting the self-punishment of hunger strike. This in turn initiated further physical ‘punishment’ through force-feeding which, owing to its widespread report in contemporary literature and illustrations, enabled the suffering body to once more assume centre stage. The suffragette in her solitary cell thus became the protagonist of her own theatrical production that was viewed by thousands.

Foucault, on the other hand, argues that following the close of the eighteenth century, bodies became unimportant in terms of punishment and were only touched in order ‘to reach something other than the body itself.’ The body was thought of as an instrument or intermediary: if one intervenes upon it to imprison it, or to make it work, it is in order to deprive the individual of a liberty that is regarded both as a right and as property. The suffragettes, however, demonstrated that the imprisoned body did not merely serve as an intermediary, but was itself a symbol of woman’s experience, damaged and starved by political inequalities. Assuming the role of their own torturers, these women inflicted punishment upon themselves in order to illustrate the injurious potential of being denied access to the public sphere. The suffragettes were thereby able to expose the extent of their political and social reduction through the spectacle of their bruised and emaciated bodies.

While Foucault writes that as an instrument, the body ‘is caught up in a system of constraints and privations, obligations and prohibitions’, the suffragettes revealed the extent to which their bodies were already constrained. The nineteenth-century woman was bound by patriarchal society, defined in terms of her body and imprisoned within the domestic sphere. Incarceration only served to exaggerate women’s social and political position, while the hunger strike called attention to female minds that were starved of education and employment.

The nineteenth-century female body is inextricably linked to punishment, politics and power. According to Foucault, the body and the ‘power relations’ with which it is invested are always central to punishment since: in our societies, the systems of punishment are to be situated in a certain “political economy” of the body…it is always the body that is at issue – the body and its forces, their utility and their docility, their distribution and their submission.

The nineteenth-century female body is inextricably linked to punishment, politics and power. According to Foucault, the body and the ‘power relations’ with which it is invested are always central to punishment since: in our societies, the systems of punishment are to be situated in a certain “political economy” of the body…it is always the body that is at issue – the body and its forces, their utility and their docility, their distribution and their submission.

These power relations are clearly played out in the case of the suffragette hunger strikes and government force-feeding, wherein the struggle to assume control of the female body accords with Foucault’s notion of power. Rather than being distributed throughout society via a ‘top-down’ system originating from a single patriarchal source, ‘power must be understood in the first instance as the multiplicity of force relations immanent in the sphere in which they operate’. The suffragettes’ power lay in their decision to embark upon a hunger strike, which in turn provoked medical response to force-feed the starving women. In the power struggle between the prison doctor and the suffragette, the hunger strike left women weak and seemingly more malleable to masculine authority. Yet, the prisoners were able to use this weakness as a form of power. Roberts write that ‘[t]he hunger strike was a species of passive resistance’, a phrase which critic Jane Marcus also uses to describe hunger striking, adding that it was a ‘weapon…used by the obviously weak against the powerful’. The suffragettes were far from weak, however, their very imprisonment suggests that they were in fact regarded as a powerful group since otherwise they would pose no threat and would not require incarceration.

It is particularly significant that the body was used as a tool to gain political status at the end of the nineteenth century, coming shortly after the diagnosis of self-starvation as anorexia nervosa in 1873 and in a century obsessed with the regulation of female bodies and women’s relation to food. W. Vandereycken and Ron Van Deth question whether ‘the self-starvation of anorexic patients perhaps served as an example? Or had anorexia itself been an expression of silent protest within the walls of the Victorian bourgeois home?’ Female self-starvation, both in the form of anorexia nervosa and the suffragette hunger strike, have the same origin. They arise as part of the battle for control of the female body within Victorian society. Suffragette prisoners and women diagnosed as anorexic both used food refusal as a weapon against patriarchal authority. Both wanted to be perceived as volitional beings, rather than the ‘weaker’ sex, defined in terms of the body and governed by its reproductive organs.

Despite the connection between anorexia nervosa and hunger strikes, however, the motives behind anorexic and hysterical self-starvation were regarded as distinct from that of suffragette prisoners. While Gull identified his patients as suffering from ‘mental perversity’ and Lasègue theorised that anorexia was hysterical in origin, suffragettes starved themselves in protest against the government’s refusal to grant them first division status. According to a report published in The British Medical Journal in 1912, this meant that they were ‘in a normal mental condition, which cannot be said of the patients who refuse food in the asylums’ since ‘there is certainly no evidence of “hysteria”’. Whereas suffragettes ceased self-starvation once they reached their political goal, the goal of the anorexic could only be achieved once patriarchy ceased its attempt to control female bodies and women’s lives in general.

Tamar Heller and Patricia Moran maintain that ‘the anorexic—like her discursive and etiological sister, the hysteric—is apparently on a hunger strike against domesticity and the lack of nourishment it provides for women, the kind of hunger for a sphere outside the domestic’. The suffragette hunger strikers campaigned for emancipation from the private sphere for all women, whereas the anorexic’s food refusal was part of an individual battle to gain control of her own body. By refusing to eat, the suffragettes transformed self-starvation from the personal to the political.

Foucault states that ‘in punishment-as-spectacle…it was always ready to invert the shame inflicted on the victim into pity or glory’. This was revived by the hunger strikers since their capacity to maintain their fasting, despite the violent force-feeding, glorified them as strong, determined individuals. Government authorities attempted to prevent this when on the 18th March, 1912 in response to a declaration that forcible-feeding should be stopped, the Home Secretary ‘firmly disagree[d], foreseeing mass suffrage martyrdom.’

With the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, self-starvation was viewed as a shameful illness that must be treated privately in the home or hospital before the patient was able to return to society. From a personal affair acted out within the privacy of the middle-class bourgeois home between the anorexic girl, her family and the attending physician, with the arrival of suffragette hunger strikers self-starvation became a public spectacle.

Unlike in the cases of anorexia nervosa, suffragette hunger striking was not the behaviour of individual women, but a political act in which many came together and starved themselves en masse. While medical practitioners and government officials considered hunger striking to be rebellious or suicidal, in reality its aim was to call attention to the political motive for what were judged as criminal offences.

but a political act in which many came together and starved themselves en masse. While medical practitioners and government officials considered hunger striking to be rebellious or suicidal, in reality its aim was to call attention to the political motive for what were judged as criminal offences.

The government and the medical establishment also held the belief that the hunger strikes were an attempt to reduce prison sentences. One physician, Dr Nesbit, writes that the hunger strikes were carried out as a method of avoiding punishment, describing the behaviour as ‘“a very cheap way of escaping the penalty of the law”’. A report published three years later, however, disagrees, stating that ‘[t]he suffrage prisoners…have never hunger struck to shorten their sentences, but only to obtain equality of prison treatment for prisoners convicted of like offences’.

Since their campaign was political, rather than personal, the imprisoned women only refused food until their demands were met. The true motives for the hunger strike are recounted by suffragettes themselves in fictional and autobiographical writings, such as K. Roberts’ ‘Some Pioneers and a Prison’, published in 1913. In her work, Roberts reveals that since petitions proved useless in gaining first division status, ‘it was determined to make a protest by politely and quietly declining to wear the prison clothes and eat the prison food’. Members of the WSPU protested ‘against second division treatment, among ordinary criminals, being given to a woman who had committed political offences.’ The narrator does not consider her actions to be ‘an offence at all’, but merely a demonstration against the inequality of government law.

Self-starvation was a protest against injustice, not only of women’s treatment in general, but of the way in which the campaign against this injustice was perceived by authority figures. In a report published in 1909, C. Mansell Moullin writes that: they are fighting for a political idea. Even the Government, though it will not treat them as political prisoners, does not venture to deny that. For this they are being treated as common criminals, in a way that men never are, and forcible feeding is resorted to because that is the only way in which the Government can make the continuance of their punishment as common criminals possible. By diagnosing suffragette behaviour as criminal, the government was able to discount women’s appeal for political power.

Similarly, a few decades earlier, physicians had diagnosed women who took control of their own bodies through self-starvation as being of unsound mind and suffering from the ‘disease’ anorexia nervosa. Nineteenth-century patriarchal structures defined what they considered to be undesirable behaviour as criminal, insane or the result of physical illness in order to justify ignoring female subjectivity. Women’s efforts to challenge the status quo through political protest or by attempting to gain ownership of their bodies were discounted by the government, which defined their actions as abnormal or dangerous and requiring imprisonment and medical treatment.

Even though the days of the body as spectacle were over, authority figures continued in their attempt to regulate and normalise the rebellious female body. In the nineteenth century, ‘a whole army of technicians took over from the executioner, the immediate anatomist of pain: warders, doctors, chaplains, psychiatrists, psychologists, educationalists’. Foucault’s argument that the executioner was replaced by the physician suggests that medical examination and treatment of the body is as violating as the pain and suffering caused by a public death.

J.S. Edkins, however, disagrees with this association, instead aiming to elevate the physician. Edkins’ remarks are one example of the opposition raised in the case of treating healthy women, writing that the use of force-feeding is ‘derogatory to the dignity of the medical profession that its members should be called in to treat with force healthy but recalcitrant prisoners.’ There is a suggestion in this of the status of the profession being removed only in degree from that of common executioner or flogging warder. According to this report, the suffragettes ought not be made to suffer the physical ‘punishment’ of force-feeding since this is beneath the dignity of the medical practioner whose job it should be to treat ill patients, rather than to administer violent procedures upon a healthy subject.

Despite this account, however, prison medical authorities did force-feed women, treating them as mere objects to be kept alive, while ignoring their mental state and subjectivity. This is exemplified in C. Lytton’s ‘Prisons and Prisoners’, the narrator of which relates that following her sixth force-feeding: ‘I complained to the doctor that the processes of digestion were absolutely stagnant. I suggested to him that he should leave out one meal, with a view to allowing the natural forces of the body to readjust themselves. The physician’s response symbolises masculine reactions to the suffragette campaign as a whole: ‘[h]e did not answer me, but turned to the head assistant…“Do you understand her? I don’t”’. Rather than treating the narrator as a reasonable being, the doctor finds her words nonsensical and he chooses to ignore her plea.

Despite this account, however, prison medical authorities did force-feed women, treating them as mere objects to be kept alive, while ignoring their mental state and subjectivity. This is exemplified in C. Lytton’s ‘Prisons and Prisoners’, the narrator of which relates that following her sixth force-feeding: ‘I complained to the doctor that the processes of digestion were absolutely stagnant. I suggested to him that he should leave out one meal, with a view to allowing the natural forces of the body to readjust themselves. The physician’s response symbolises masculine reactions to the suffragette campaign as a whole: ‘[h]e did not answer me, but turned to the head assistant…“Do you understand her? I don’t”’. Rather than treating the narrator as a reasonable being, the doctor finds her words nonsensical and he chooses to ignore her plea.

The suffragette’s perceivably incomprehensible words match her ‘irrational’ actions. The female language of self-starvation is dismissed by patriarchal authority as the ramblings of a lunatic. Some physicians diagnosed self-starvation itself as the symptom of an unbalanced mind, Dr Nesbit stating that: [i]f an otherwise healthy individual refuses food to the injury of her health and danger to her life, she is without doubt to my mind temporarily insane, just as much as a person taking a dose of poison in similar circumstances. Let the idea be what it may—political or otherwise—the mind is unhinged, and the individual must be guarded against herself. Forcible-feeding was thus justified by diagnosing hunger striking as the result of insanity, the subject’s lack of rational thought suggesting that she is incapable of decision making and does not really intend self-harm.

Richard Smith points to the ethical implications involved in allowing the hunger strike to continue: ‘even though he might start his strike in his right mind, sometime before he dies (and usually only very shortly before) he loses his faculties. How then for the next few days can the doctor continue to be sure that the prisoner knows what he is doing and wants to continue? He cannot.’ It may be questioned why women chose a form of protest that deliberately reduced and weakened their bodies, thus confirming patriarchal views that women were too frail to be granted political power. According to Adrienne Munich: they may have been responding, in part, to seductions of a dominant middle-class culture that claimed that women’s bodies, as well as political aspirations, should be small and subject to regulatory control. I add that the suffragettes challenged this masculine version of the ideal woman by using their physical fragility as a power mechanism to make a political statement. By purposefully weakening their bodies, the hunger strikers demonstrated, in an extreme form, the state in which they were kept by those who demanded their restriction to the private sphere. The vote would therefore enable women to exercise their full potential and develop as subjective individuals, rather than being reduced and inhibited by government law.

This was symbolised in suffrage propaganda, which Linda Schlossberg notes, ‘frequently imagines the vote itself  to be a kind of sustenance’. Denied a voice, the suffragettes called attention to the fact that their political exclusion was a form of intellectual starvation. Their political non-existence thus became physically expressed through their wasting bodies. Self-starvation was not only a political statement; it was also a method of self-control achieved through refusing physical penetration. The politics of desire are made apparent in the practices of self-starvation and force-feeding. The closed mouth frustrates the opponent’s desire by refusing entry, while simultaneously preventing the subject from satisfying their own hunger or sexual desire. The subject and the object cannot access or satisfy their desire if one of the bodies is impenetrable.

to be a kind of sustenance’. Denied a voice, the suffragettes called attention to the fact that their political exclusion was a form of intellectual starvation. Their political non-existence thus became physically expressed through their wasting bodies. Self-starvation was not only a political statement; it was also a method of self-control achieved through refusing physical penetration. The politics of desire are made apparent in the practices of self-starvation and force-feeding. The closed mouth frustrates the opponent’s desire by refusing entry, while simultaneously preventing the subject from satisfying their own hunger or sexual desire. The subject and the object cannot access or satisfy their desire if one of the bodies is impenetrable.

The nineteenth-century woman was able to use refusal in order to gain power by maintaining ownership of her body, rather than surrendering it to her husband, doctor or prison authority. By closing the body and denying entry to external ideas, hunger-striking also served as a symbol of resistance to notions of women as weak, passive and inferior to men.

Conversely, feeding was a metaphor for the forced ingestion of patriarchal concepts of womanhood. The pain caused by forcible-feeding is symbolic of the damage inflicted upon women by these ‘ideals’ of Victorian femininity. Frustrating desire and causing immense suffering, the masochism of hunger-striking is referred to by Lady Constance Lytton as ‘“the weapon of self-hurt”’. Sylvia Pankhurst describes the discomforting experience of hunger strike, speaking of pains in the back, chest and stomach, lack of circulation and palpitations as ‘gradually the feeling of weakness and illness grows.’ Every day, she is able to perceive ‘that one has grown thinner, that the bones are showing out more and more clearly, and that the eyes are grown more hollow.’ Following release from prison, many suffragettes continued to experience problems with digestive functions and suffered from headaches and nervous symptoms.

The sacrifice involved in the suffrage campaign did not only include self-starvation, but even extended to suicide. In June 1912 during a mass force-feeding in Holloway Goal, Emily Wilding Davidson threw herself down a staircase, while the following year she cast herself under the King’s horse and was crushed to death.

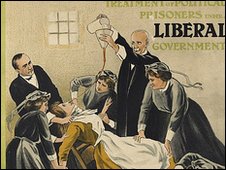

These efforts were undermined, however, by the introduction of forcible-feeding. Patriarchal authorities attempted to neutralise the physical effects of the hunger strike, and the protest that it represented, by robbing suffragettes of a weapon that did not conform to masculine discourses of power. In 1909, 36 of the 110 hunger-striking suffragettes were force-fed. Like the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa in 1873, forcible-feeding of hunger striking prisoners was a method of controlling women’s bodies. In the British Medical Journal (1912), the Home Secretary stated that ‘force feeding was instituted by him to keep the suffrage prisoners in health’. He also assured that ‘the practice of forcible feeding is unattended by danger or pain,’ yet both were found to be untrue.

Forcible-feeding was put into practice in order to avoid death, while the process of feeding itself was painful and injurious. Prior to 1974 when the Home Secretary declared that ‘a prison medical officer would not be neglecting his duty if he did not feed a prisoner against his will’, there was considerable debate as to whether forcible-feeding should be carried out.

Forcible-feeding was put into practice in order to avoid death, while the process of feeding itself was painful and injurious. Prior to 1974 when the Home Secretary declared that ‘a prison medical officer would not be neglecting his duty if he did not feed a prisoner against his will’, there was considerable debate as to whether forcible-feeding should be carried out.

Some were concerned that allowing a prisoner to starve themselves to death meant that the supervising authority would be held responsible. One physician questioned: whether if a prison doctor provided substantial meals for a prisoner, but never bothered himself whether they were eaten or not, and the prisoner eventually died of starvation, the doctor could be held to be an accessory before the fact to suicide. In response, Mr Burrows stated that: it was a well-known principle of the Common Law that, where one person was in charge of another, who could not help himself or herself, there was an obligation on the person in charge to see that that person was properly fed and had proper attention. It became a concern that if women were left to starve, this would ‘bring the officials into conflict with a large number of prison rules’. The motivation for feeding the women was thus self-interest on the part of the attending physician who did not wish to be charged with manslaughter.

Others believed that it was their medical duty to sustain the prisoners’ lives, Dr Collingwood stating that ‘he feels that the only function of a medical officer as such is to prevent loss of life’. Unlike modern law which acknowledges ‘that a competent prisoner may choose to commit suicide by starvation’, suffragettes were not permitted to starve themselves to death. While in today’s society intervention only occurs when a prisoner is unable to make an informed decision, force-feeding took place on a regular basis in the case of the suffragette hunger strikes. During one case, Leigh v Gladstone, a woman who was forcibly-fed ‘later attempted to sue for trespass’ and was unsuccessful since it was perceived by the court as the doctor’s duty to prevent her death: Lord Alvestone, Lord Chief Justice, directed the jury, saying: “…as a matter of law it was the duty of the prison officials to preserve the health of the prisoners, and a fortiori to preserve their lives…”

Prior to the suffrage campaign, self-starvation was often used as a method of suicide in the Victorian prison. In  his account, Philip Priestly records that ‘“[o]bstinate refusal of food, and an attempt to die by starvation were of common occurrence…always to be overcome by forcible feeding.”’ Force-feeding in this case was justified by claiming that it prevented the ‘crime’ of constant food refusal, since to starve oneself to death was regarded as a form of suicide. In one report written a few months following the onset of the hunger strikes, it is stated that self-starvation must be prevented since it is a form of suicide and therefore a criminal action: [i]f prisoners are kept in prison, it is clearly the duty of the authorities to prevent them committing other felonies, and it must not be forgotten that suicide is a felony. Thus, force-feeding was justified in these cases as being carried out in the name of duty and preventing crime.

his account, Philip Priestly records that ‘“[o]bstinate refusal of food, and an attempt to die by starvation were of common occurrence…always to be overcome by forcible feeding.”’ Force-feeding in this case was justified by claiming that it prevented the ‘crime’ of constant food refusal, since to starve oneself to death was regarded as a form of suicide. In one report written a few months following the onset of the hunger strikes, it is stated that self-starvation must be prevented since it is a form of suicide and therefore a criminal action: [i]f prisoners are kept in prison, it is clearly the duty of the authorities to prevent them committing other felonies, and it must not be forgotten that suicide is a felony. Thus, force-feeding was justified in these cases as being carried out in the name of duty and preventing crime.

Some medical authorities, however, were of the opinion that no intervention should be given in the case of hunger strike. Edward Thompson, Surgeon at Tyrone County Hospital, wrote in 1909 that ‘the duties of medical officers of prisons are, or should be, confined entirely to the treatment of sick prisoners’. According to this report, self-starving women should not be treated since their behaviour was not the result of illness. It was argued that the suffragettes should instead be permitted to assert control over their own bodies given that they are ‘political prisoners, and therefore should be allowed to do much as they please.’

In addition to these arguments, Bea Brockman writes that the forcible-feeding of suffragettes was ‘justified on paternalistic grounds…As in all paternalistic judgements, it was felt that the doctor “knows best”. The physicians who carried out the feeding did not ‘know best’ however. According to The British Medical Journal they ‘were acting practically as prison warders, and were putting their medical skill to an improper use by carrying out forcible feeding against the wishes of the patients.’ During the hunger strikes, doctors behaved unprofessionally as controlling authorities. Instead of acting in the best interests of the patient, they removed their autonomy in what equated to physical abuse. The British Medical Journal records that ‘[t]he public trusts in the profession, and has great faith in “medical treatment”’: by force-feeding suffragette prisoners, however, this trust was abused.

In Discipline and Punish, Foucault states that ‘there may be a “knowledge” of the body that is not exactly the science of its functioning, and a mastery of its forces that is more than the ability to conquer them’. The medical and legal establishments claimed to possess knowledge of the female body, which in turn was used in the subjection of women. Since, according to Foucault, ‘power and knowledge directly imply one another’, this ‘knowledge’ of women placed men in a position of power over their female patients. Law, medicine and the regulation of women’s bodies are combined in the case of forcible-feeding, J. Price Williams writing that ‘[t]he fact that prison doctors are constables explains how this abuse has arisen, but does not justify it.’

The suffragettes were imprisoned by legal and medical authorities who exploited their power in order to dominate others: [t]he Constable-doctor comes to the aid of the Government with his skill as a doctor, his power as a constable, and, using the term “medical treatment” as a cloak, commits an act which would be an assault if done by any ordinary doctor. Using this ‘cloak’ of authority, the physician was able to control women by diagnosing their bodies as sick and in need of treatment, thereby forcing their submission to patriarchal authority.

Prior to the forcible-feeding of suffragette prisoners, anorexia nervosa and hysteria were treated in a similar fashion. In the nineteenth century treatment of anorexia, the patient was often removed from her family, superintended by nurses and provided with food at regular intervals. In the case of ‘Miss K. R—, aged fourteen’, reported by William Gull in 1888, ‘[a] nurse was obtained from Guy’s, and light food ordered every few hours’. Although Gull himself did not admit to using force-feeding, ‘[p]ublished clinical reports from doctors of lesser status…reveal that force-feeding was not uncommon in cases of anorexia nervosa’. An issue of the Lancet in 1888 states that one patient who ‘went to live in a farmer’s house some miles away, was forced to take “plenty of milk and fresh eggs,” and came home very much improved.’ In the same year, the journal published notes on the case of a nine year old girl who was also forcibly-fed: [s]mall quantities of liquid food were ordered to be given to her frequently; for a few times she voluntarily swallowed it, but on the 7th she became stupid, and everything had to be administered to her forcibly.

Force-feeding anorexic patients was not always successful, however. A report in an 1895 issue of the Lancet described a fatal case of anorexia. The patient refused food so ‘was fed an enemata of peptonised milk, beef tea, and brandy.’ This was carried out for two to three days and ‘[i]n ten days she could take a moderate diet by the mouth, but suffered from diarrhoea. On the thirteenth day after admission she rapidly became worse, the temperature rose to 102°F, and on the fifteenth day she died.’

Forcible-feeding was also performed in lunatic asylums upon women who refused to eat. In the case of hysterical patients, however, feeding was sometimes employed by the physician for their own financial gain and to secure a successful reputation. Joan Jacobs Brumberg states that ‘the medical entrepreneurs who ran the private asylums turned to the same procedures when they faced an intractable patient whose parents were paying handsomely to see her weight increase.’

In some cases, the threat of force-feeding was sufficient to encourage a hysterical woman to cease her starvation. J.A. Campbell, Superintendent of the Garlands Asylum in Carlisle, writes in The British Medical Journal (1878): [c]onsiderable numbers of girls in the hysteric state, who had refused food at home, when they were brought here, and the means and manner of giving it were explained to them, have at once given in and taken their food. I always make a point of taking such patients to see another fed with the pump. In order to discourage them from taking up the practice of self-starvation, asylum doctors ensured that new patients observed other women being forcibly-fed.

While this was often a successful method of prevention in the case of hysterical women, the threat of punishment failed to deter the suffragettes from their political hunger strike. The self-punishment of starvation and subsequent physically punishing practice of force-feeding was welcomed by the suffragettes because it drew attention to their campaign. Unlike hysterical and anorexic patients, members of the WSPU did not give in when faced with force-feeding but instead suffered for their cause. By utilising forcible-feeding, patriarchal authorities refused to acknowledge the political dimension of the suffragette starvation.

As in the case of anorexia nervosa, the prison doctor judged that treatment had been successful and the patient ‘normalised’ when her body no longer displayed signs of emaciation. Only the symptoms of the hunger strikes were treated, revealing that patriarchal perspectives upon women and their bodies underwent little alteration during the second half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. In the struggle against political exclusion, the suffragettes’ bodies were bruised and battered in their arrest, and subsequently imprisoned, starved and force-fed. Yet, the authorities only saw emaciated bodies that could die under their supervision.

‘normalised’ when her body no longer displayed signs of emaciation. Only the symptoms of the hunger strikes were treated, revealing that patriarchal perspectives upon women and their bodies underwent little alteration during the second half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. In the struggle against political exclusion, the suffragettes’ bodies were bruised and battered in their arrest, and subsequently imprisoned, starved and force-fed. Yet, the authorities only saw emaciated bodies that could die under their supervision.

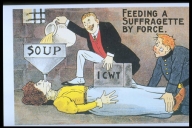

The process of force-feeding is graphically described in contemporary journals and works of fiction. In ‘Forcible Feeding of Suffrage Prisoners’ published in 1912, the authors disclose that ‘[t]he feeding cup method is frequently forcibly administered solely by the wardresses, without the supervision of a qualified medical practioner.’ The procedure was often carried out by women in which the wardresses became the agents of the patriarchs, carrying out their work. Women’s bodies were held down and restrained by other women’s bodies, the very bodies that the suffragettes fought to liberate. The force-feeding was violent and brutal, a power struggle of physical strength that symbolised the suffragettes’ political and social battle: [d]uring the struggle before the feeding, prisoners were held down by force, flung on the floor, tied to chairs and iron bedsteads. As might be expected, severe bruises were thus inflicted. The prisoner’s arms that were ‘held firmly, so that she could not move’ represent the restraints placed upon women by early twentieth-century society, while the bruises are visible marks of their suffering, both mental and physical.

It was not only the act of force-feeding itself that was injurious, there were many side effects. A report in the British Medical Journal states that ‘[i]n most cases local frontal headache, earache, and trigeminal neuralgia supervened, besides severe gastric pain, which lasted throughout the forcible feeding, preventing sleep.’ Choking, vomiting, palpitation, faintness, and cold temperature were common, while in one case, food was accidentally injected into the lung.

In accounts of forcible-feeding, the mouth is often the focal point of the procedure, Agnes Savill and Victor Horsley recording that ‘[w]hen the oesophageal tube was employed the mouth was wrenched open by pulling the head back by the hair over the edge of a chair, forcing down the chin, and inserting the gag between the teeth.’ During the feeding ‘the lips, inside of the cheeks, and gums were frequently bruised, sometimes bleeding and sore to touch for days after.’ The mouth becomes stopped up with food in order to prevent speech, its bleeding a symbol of how the female voice was damaged by those who did not heed its words and instead demanded its silence. The injured mouth not only represents the wounded voice, its closure also suggests a refusal to be penetrated. If this is the case, as critics such as Jane Marcus have noted, ‘[t]he depictions of forcible feeding on several suffragette representations may be clearly read as rape scenes.’ The brutality of rape is depicted during the feeding, as the mouth was forced open ‘by sawing the edge of the cup along the gums’, while ‘[t]he nasal mucus membrane was frequently lacerated’ and the process left the ‘throat…swollen and sore’. The throat became the vaginal passageway which was torn and injured during the force-feeding, pointing to the sexual abuse that women’s bodies suffered at the hands of men.

In accounts of forcible-feeding, the mouth is often the focal point of the procedure, Agnes Savill and Victor Horsley recording that ‘[w]hen the oesophageal tube was employed the mouth was wrenched open by pulling the head back by the hair over the edge of a chair, forcing down the chin, and inserting the gag between the teeth.’ During the feeding ‘the lips, inside of the cheeks, and gums were frequently bruised, sometimes bleeding and sore to touch for days after.’ The mouth becomes stopped up with food in order to prevent speech, its bleeding a symbol of how the female voice was damaged by those who did not heed its words and instead demanded its silence. The injured mouth not only represents the wounded voice, its closure also suggests a refusal to be penetrated. If this is the case, as critics such as Jane Marcus have noted, ‘[t]he depictions of forcible feeding on several suffragette representations may be clearly read as rape scenes.’ The brutality of rape is depicted during the feeding, as the mouth was forced open ‘by sawing the edge of the cup along the gums’, while ‘[t]he nasal mucus membrane was frequently lacerated’ and the process left the ‘throat…swollen and sore’. The throat became the vaginal passageway which was torn and injured during the force-feeding, pointing to the sexual abuse that women’s bodies suffered at the hands of men.

The nineteenth- and early twentieth-century female body was used for sexual purposes and to bear children, both of which caused internal physical harm. Despite the critics who define this procedure as rape, however, I would argue that to do so marginalises self-starvation as an act of political agency. The suffragettes could choose whether or not to eat and were aware of the consequences of not doing so. Suffragettes permitted themselves to be violated as since they could have discontinued the hunger-strike at any point, force-feeding could have been prevented.

The fact that the self-starvation was sustained is an indication of women’s power in which they compelled prison doctors to create suffragette martyrdom through repeated force-feeding. To simply view the procedure as rape fails to account for this element of choice and instead subscribes to the conventional power dynamic which the suffragettes intended to resist.

Often, however, forcible-feeding failed to increase the prisoner’s weight and health. A report in The British Medical Journal states that: ‘[h]owever successful it may have proved in patients suffering from other diseases, the experience of the last year or two seems to prove pretty conclusively that it fails very frequently, if not always, in the case of the suffragist hunger strikers’. The phrase ‘other diseases’ suggests that the suffragettes’ self-starvation was regarded as an illness that ought to be pathologised, treated and thereby controlled. This echoes the diagnosis of self-starvation as anorexia nervosa in 1873.

Stating that self-starvation is a physical condition, a ‘disease’, the report later claims that it is a mental decision capable of affecting physicality: ‘[i]t seems quite possible that digestion, absorption, and assimilation may all be more or less inhibited by an effort of the will’. According to this, suffragettes were able to volitionally hinder digestive processes, suggesting that self-starvation was controlled by the subject. This contradicts the article’s earlier classification of self-starvation as a disease.

Despite these assertions, the hunger-striking could not be ‘cured’ since it was not an illness, nor did women have control over their digestive functions. Suffragette food refusal was politically motivated and this behaviour was repeated until their demands were met. This article reduces the political to the physical in stating that it is otherwise.

The female body as an object to be fought over is symbolically portrayed by what became known as the Cat and Mouse Act. Introduced on March 25th 1913, the Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Bill was ‘[a]imed specifically at the suffragettes, the law enabled the government to release a hunger-striking prisoner and reincarcerate her after she recovered’. Suffragettes were released from prison, to return when their health was restored. Once back in prison, however, the hunger strike would resume, this cycle of imprisonment and release driven solely by the body. In 1912, it was stated in the House of Commons that: of 102 cases of prisoners who joined in the hunger strike we have investigated, forty-six were released long before the termination of their sentences, because their health had been so rapidly reduced as to alarm the medical officers. The language of the act posits women as mice, victims pursued by the government. Women become prey, consumable objects to be caught, toyed with and finally gobbled up by patriarchal authorities, a process which Sylvia Pankhurst found to grow ‘[i]ncreasingly wearying and painful’.

On October 21st 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst delivered a speech in New York entitled ‘Why We Are Militant’, during which she referred to the suffrage campaign and subsequent imprisonment as a ‘battle’. The battle for control of the female body at the outset of the twentieth century came to involve the diametrically opposed behaviours of female hunger striking and masculine forcible-feeding. Speaking of the ‘joy of battle and the exultation of victory, Emmeline Pankhurst expressed the enjoyment of fighting to reclaim women’s minds and bodies. Suffragettes used their bodies to fight for their minds, they were ‘women fighting for a great idea’. Their cause was social, aiming ‘for betterment of the human race’, even though the methods that they chose to achieve it were considered anti-social and rebellious. The betterment of the human race was achieved ‘through the emancipation and uplifting of women.’ The battle for control of the female body was injurious to the bodies of those who fought, yet it was in order to secure a better life, for the minds and bodies of the women who were to follow: [t]he battle cost the lives of a few, and the health of most of those who went through it: but it has secured slightly better conditions and a different status for political prisoners in the future. It is a thing that we can always be proud that even—even after forcible feeding was permitted, or, rather, ordered by the Home Secretary—not one of our women gave in. The suffragettes who engaged in the hunger strikes of 1909 did not act in vain because in 1928, women over twenty one were granted the vote.

On October 21st 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst delivered a speech in New York entitled ‘Why We Are Militant’, during which she referred to the suffrage campaign and subsequent imprisonment as a ‘battle’. The battle for control of the female body at the outset of the twentieth century came to involve the diametrically opposed behaviours of female hunger striking and masculine forcible-feeding. Speaking of the ‘joy of battle and the exultation of victory, Emmeline Pankhurst expressed the enjoyment of fighting to reclaim women’s minds and bodies. Suffragettes used their bodies to fight for their minds, they were ‘women fighting for a great idea’. Their cause was social, aiming ‘for betterment of the human race’, even though the methods that they chose to achieve it were considered anti-social and rebellious. The betterment of the human race was achieved ‘through the emancipation and uplifting of women.’ The battle for control of the female body was injurious to the bodies of those who fought, yet it was in order to secure a better life, for the minds and bodies of the women who were to follow: [t]he battle cost the lives of a few, and the health of most of those who went through it: but it has secured slightly better conditions and a different status for political prisoners in the future. It is a thing that we can always be proud that even—even after forcible feeding was permitted, or, rather, ordered by the Home Secretary—not one of our women gave in. The suffragettes who engaged in the hunger strikes of 1909 did not act in vain because in 1928, women over twenty one were granted the vote.

Copyright © 2011 Victoria Fairclough